Cooking Kohlrabi: A Humble Vegetable Rich in Tradition

Bulbous and green with antennae-like leaves, the kohlrabi almost resembles a cartoon alien rather than the brassica vegetable that it is. Also called German turnip or turnip cabbage, this cultivar of wild cabbage is not typically found in supermarkets. Instead, it shows up at specialty grocers or farmers markets.

Kohlrabi, which ranges in color from pale green to purple, can be eaten raw or cooked, from its broad leaves to its hearty stems and bulbs. My Sicilian grandmother used the whole vegetable in soups and stews; she ate it frequently in Sicily.

Kohlrabi has been eaten in Italy since at least 1554, when Siena-born botanist Pietro Adrea Mattioli wrote that the vegetable had “come lately into Italy.” Not long after, kohlrabi spread to North Europe and was being grown in England, Germany, Austria, Italy, Spain, Tripoli, and parts of the eastern Mediterranean.

I recently stumbled on a blog post by Marisa Raniolo Wilkins of All Things Sicilian and More about the ways kohlrabi is eaten in Sicily.

I reached out to Marisa, who is based in Australia, to learn more about her background and experience with this vegetable. She shared her reflections on kohlrabi’s significance in Sicilian cuisine and her favorite kohlrabi recipes.

Where is your family from in Sicily, and how did you end up in Australia?

My Sicilian background is a blend of two Sicilian regions—Catania and Ragusa—and enriched my very different life in Trieste. My mother was born in Catania but moved to Trieste when she was just five years old. When she was fourteen, life for my mother changed when my grandfather died, prompting part of her family to return to Sicily, primarily to Augusta, while she chose to stay with her eldest brother and his wife in Trieste. One other brother also remained in Trieste.

My father met my mother while stationed in Trieste during World War II. They traveled briefly to Sicily, where they married in Catania before returning to Trieste. Although the war had ended, Trieste remained in political and military turmoil through what was, for all intents and purposes, a civil war. And during her pregnancy, my mother felt unsafe. So, in the last weeks of her pregnancy, my parents caught a train to Sicily, and I was born in my paternal grandparents’ home in Ragusa. A few weeks later, they caught the train home to Trieste, where I grew up, and remained until we came to Australia.

Our family was deeply connected to our Sicilian roots, spending summers in Sicily and welcoming relatives who visited us in Trieste. My maternal grandmother would stay with us for a month, filling our home with the scents and flavors of her Catanese cooking, especially seafood. My mother’s family has always been tied to the sea, whether in Catania, Trieste, or Augusta, and much of my culinary knowledge about fish comes from her family. My fondness for eating fish partly contributed to my book Sicilian Seafood Cooking (now out of print).

When I was eight, we sailed to Australia, driven by my father’s spirit of exploration. We went directly to Adelaide, which was chosen as a city reminiscent of Trieste’s size rather than a larger city like Sydney or Melbourne. Despite our new life, we continued to make regular trips back to Italy, both to Trieste and Sicily, further deepening my appreciation of my heritage. As an adult, I made regular trips to Italy and explored many other regions—and other countries.

I feel fortunate to have been exposed to regional Italian and Sicilian cuisines with all their variations. Traveling to different countries and living in Australia have exposed me to the wealth of multicultural cuisines that are evident in this country. My knowledge, experiences, and opportunities to make connections between cuisines have enriched my understanding and appreciation of Sicilian cooking and its flavors. Sicilian cuisine remains unique due to its historical influences, ingredients, and methods of cooking.

What inspired you to write about kohlrabi’s role in Sicilian cuisine?

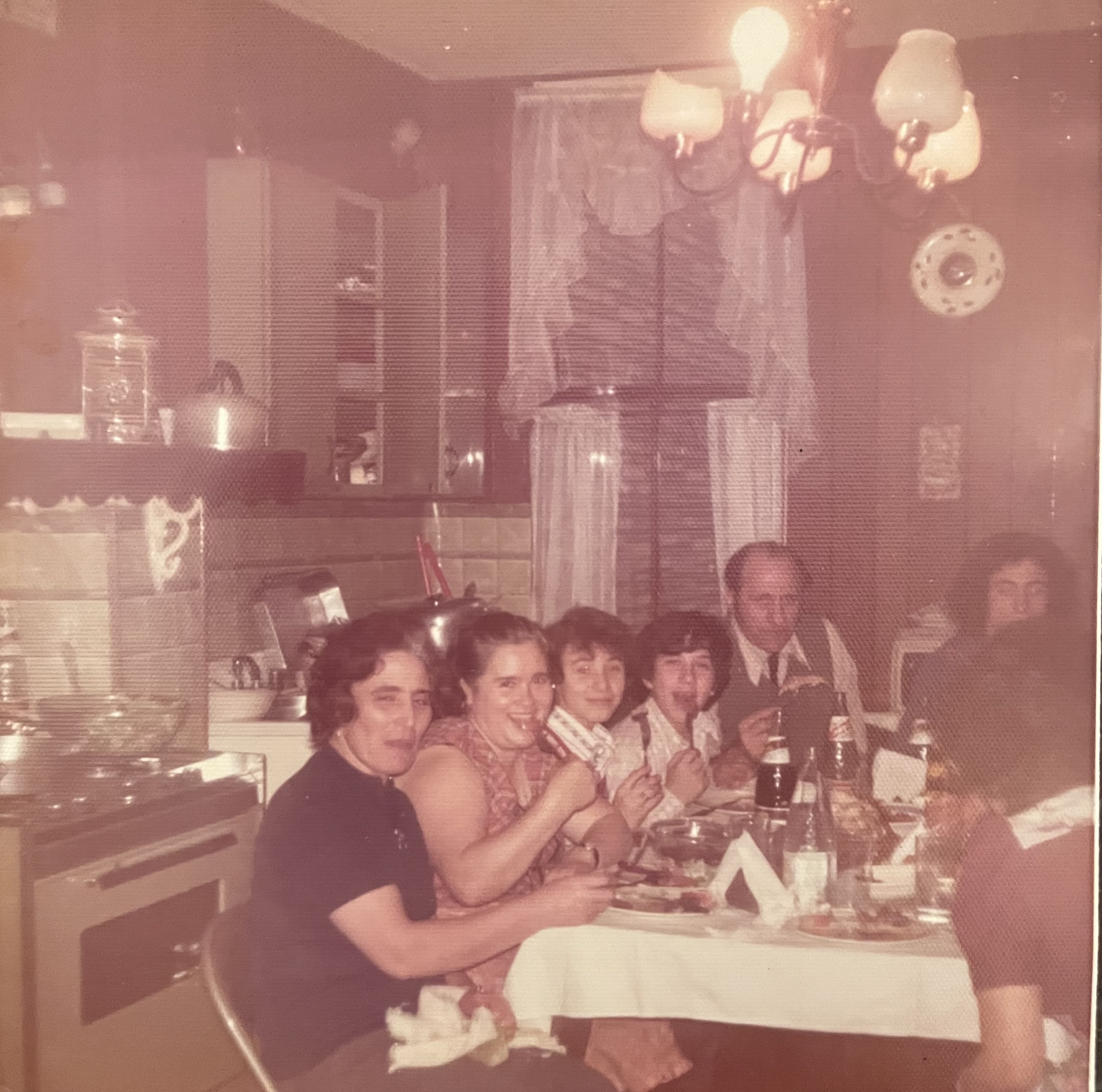

My inspiration to write about kohlrabi and its role in Sicilian cuisine stems from the memorable family tradition of cooking this vegetable in Ragusa, my father’s hometown.

The significance of kohlrabi in his family went beyond cooking this vegetable. Kohlrabi was a centerpiece of family feasts that brought everyone together, including the buying of the vegetables, the preparation, and the sharing of the cooked meal with the family.

Regarding the purchasing of the vegetable, my father’s two sisters (my two aunts) and one cousin who lived on different floors of the same building purchased their vegetables and fruit from a trusted local traveling ortalano (seller of fruit vegetables), who came around every morning—excluding Sunday—with his van. Each time I visited my Sicilian aunts in Ragusa, I had this unique experience where the squawk of the ortolano was heard from the street below their apartments, announcing his arrival. When it was in season, the leafy bunches of kohlrabi were such prized produce.

Out would come their purses and their baskets tied to the end of a rope, and they’d go to their balconies where they questioned the ortolano in detail about the quality of his produce. If satisfied, they lowered their baskets, which he filled. They hauled them back up, examined the contents, and only then, if convinced, lowered their basket once again with the money tucked inside it. Then, the aunties would make special requests for the next day, entreating him to visit them first so that they had the best produce. Sometimes, they traveled down to the van in their slippers and dressing gowns.

Then, there was the preparation of the kohlrabi. I have particularly fond memories of one of the Ragusa aunts, a remarkable cook who implemented the cooking and eating of this special dish. She is a champion pasta maker and ensured there was fresh pasta for family gatherings. The kohlrabi dish always featured a distinctive pasta known as causunnedda, the regional Sicilian name for this short pasta shape. The atmosphere of these family gatherings was gratifying. There was laughter, stories, fondness for the family, and the pleasures associated with sharing the meal and eating something delicious.

Kohlrabi are called cavoli in Sicily; in Italian, it is known as cavolo rapa. Cavolo is the generic term for some of the brassicas; for example, cavolo verza is a cabbage, cavolo nero is Tuscan cabbage, cavolo rosso is red cabbage, and in Italian, cavoli are cauliflowers. (Just to confuse things even further, Sicilians call cauliflowers broccoli.)

In the Ragusa family, they referred to the whole dish as causunnedda. I am assuming this was the abbreviation of causunnedda chi cavoli (Sicilian), causunnedda with kohlrabi.

How can one forget and not celebrate these memories?

The Ragusani are known for their straightforward, flavorful dishes, which focus on local produce, rich meats—especially pork—and seasonal vegetables. This emphasis on simplicity has profoundly shaped my understanding of cooking, showing me that the best meals often come from the freshest ingredients and heartfelt traditions.

Spending time with my father’s family, particularly with this aunt, has further deepened my passion for Sicilian cooking. She has been a treasure trove of knowledge, eager to share recipes and techniques, knowing how much I cherished my heritage. Through her stories and guidance, I’ve come to appreciate the intricate web of flavors, customs, and memories that define Sicilian cuisine—making kohlrabi not just a vegetable but a symbol of family connection and culinary history.

How significant is kohlrabi in Sicilian cuisine compared to other vegetables?

Kohlrabi’s significance in Sicilian cuisine may be modest compared to more popular common vegetables like tomatoes, peppers, eggplants, or green leafy vegetables (this includes wild greens).

What is unique in the cooking of this vegetable is the emphasis placed on the kohlrabi leaves, often considered more valuable than the bulb itself. They are sold in bunches; the bulbs are smaller than I have found in Australia, and there are many leaves. There are purple-colored kohlrabi and light green. What I experienced in Ragusa were the light green ones, whereas in Syracuse, they were an attractive purple with some green. In Australia, at least in Melbourne, where I live, I have only seen green ones.

Purple kohlrabi. Photo by Marisa Raniolo Wilkins

How does kohlrabi use vary regionally?

While my mother’s side of the family excelled in their own culinary traditions, I didn’t encounter kohlrabi in her family. Instead, it was in Ragusa that I truly came to appreciate its significance.

In Sicily, as in other parts of Italy, kohlrabi is often simply boiled, drained, and then presented as a cooked salad, dressed with a generous drizzle of extra virgin olive oil, a sprinkle of salt, and either lemon juice or vinegar. This method, while straightforward, showcases the humble quality of the ingredients.

In the fertile region of Acireale, just north of Catania and rich with the volcanic soil of Mount Etna, kohlrabi takes on a different role. Here, it’s not just a simple side dish but a flavorful dressing for pasta. The vegetables (bulb and leaves) are boiled and drained, and the cooking water is preserved to cook the pasta. The drained vegetables are sautéed in hot oil with garlic and chili that creates a vibrant dish that might also include a splash of tomato for added depth. I recently contacted my cousin in Augusta, just south of Catania, who said that she follows a similar method but enriches the depth of flavor with anchovies during the sautéing process, illustrating the creativity inherent in Sicilian cooking.

What sets Ragusa apart is how the Ragusani relatives have a distinct way of cooking it. They use homemade causunnedda, but they also add fresh pork rind to the water while cooking the kohlrabi, infusing it with the rich flavor of the homemade broth.

The causunnedda is then cooked in this flavorful broth, which transforms it into something delicious, turning a humble vegetable into a celebration of local flavors and family heritage.

In my mother’s family, broth is typically made with chicken, veal, or beef—never fresh pork. This stark contrast highlights how regional traditions shape our understanding of food. These traditional methods and unique techniques not only enrich the dish, but also weave a narrative of family, community and culture.

What is your favorite way to prepare and enjoy kohlrabi?

My favorite way to prepare and enjoy kohlrabi is a blend of tradition and creativity inspired by both my Sicilian roots and modern culinary trends. Here in Australia, kohlrabi has sparse green leaves, which is a departure from the leafy bunches I remember from Sicily. When I do come across kohlrabi with its leafy greens intact, it becomes a richer experience.

I treat the leaves much like I would cook cime di rapa or broccoli in a classic pasta dish with the greens and bulb sautéed with garlic and a little chili. Often, I have had to buy bunches of kale to increase the number of green leaves. Recently, my cousin in Augusta shared a brilliant tip of also adding anchovies while sautéing the vegetables. I do this often when I am preparing other vegetables, and it makes sense to do this with kohlrabi. I am looking forward to trying this.

Of course, I’ve also embraced contemporary ways of preparing kohlrabi, especially with exposure to how it is prepared in other countries. I like it in crisp salads or rich soups, showcasing its versatility. But there’s something profoundly satisfying about returning to those old Sicilian traditions, reminding me of family meals where ingredients and preparation were cherished. Each preparation tells a story—of the past, family, and the flavors that unite us across time and distance.

What do you hope readers will take away from your recipes?

What I hope readers will take away from my recipes is a rich tapestry of connection, nostalgia, and inspiration. For those who have traveled to Sicily, I would like them to remember their culinary adventures and the vibrancy and beauty of Sicily.

For readers unfamiliar with Sicilian cooking, I hope to introduce them to its unique flavors and traditions, exemplifying how it diverges from the more commonly known Italian cuisine and its regions.

Many of my readers are second-generation Sicilian Americans who cherish the recipes and stories that connect them to their heritage. I hope my recipes spark memories of family gatherings, the aromas in their grandparents’ kitchens, and the warmth of shared meals. Sharing these recipes would be very rewarding if they not only valued those memories, cooked those recipes, and also passed on the traditions to the next generation.

Cooking becomes more than just a task; it transforms into a celebration of culture and history. Therefore, most of all, I would like to inspire curiosity about Sicilian cuisine and to motivate them to explore its diverse ingredients and techniques. Cooking Sicilian recipes should increase understanding of the broader regional variations within the cuisine of Italy.

>>Get Marisa’s wet pasta dish with kohlrabi recipe here!<<

If you enjoyed this article, consider subscribing to my newsletter for more content and updates!