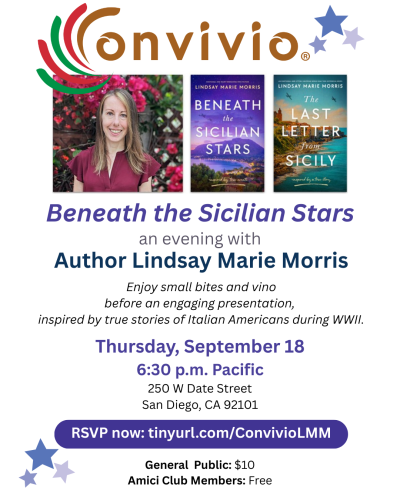

How One Young Leader Is Reviving Italian-American Heritage

The bulk of Italian immigration to the United States occurred between 1880 and 1920, with approximately 4 million Italians arriving during this period, mainly from Southern Italy and Sicily. That means most Italian Americans are at least four generations removed from their Italian heritage.

Traditions fade along with those connections. It’s no wonder that one of the most pressing concerns among cultural organizations is how to reach and inspire younger audiences.

At 27 years old, Patrick Ross Campesi bucks the trend.

While many of his peers may feel distanced from their roots, he’s spent the past five years leaning in. It all started with the passing of his Sicilian grandfather in 2016 and a desire to better understand and embrace his legacy. He began researching his genealogy, learning more about his great-great-grandparents, who emigrated from the Trapani area to the United States in the 19th century and found work as sugarcane farmers in Louisiana.

About five years ago, Patrick decided he could do more and help other Italian Americans connect with their heritage. He’s since taken on leadership roles with St. Expedite Lodge Order of the Italian Sons and Daughters of America, American-Italian Federation of the Southeast, and Italian American Future Leaders. In 2023, he founded the Louisiana Italian American Heritage Foundation, for which he serves as president.

Patrick shared his experience, present and future challenges, and what he hopes to give back to the greater Italian American community.

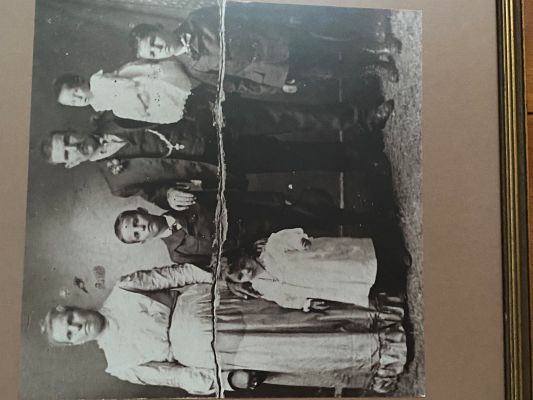

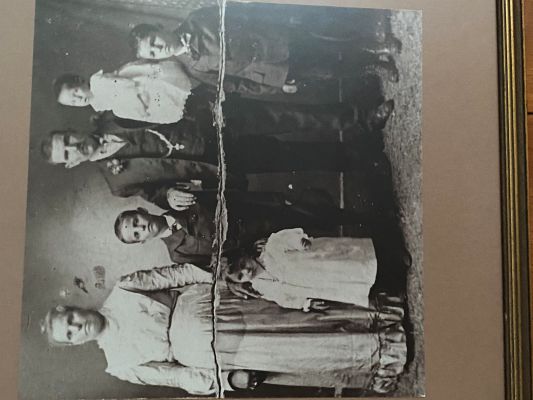

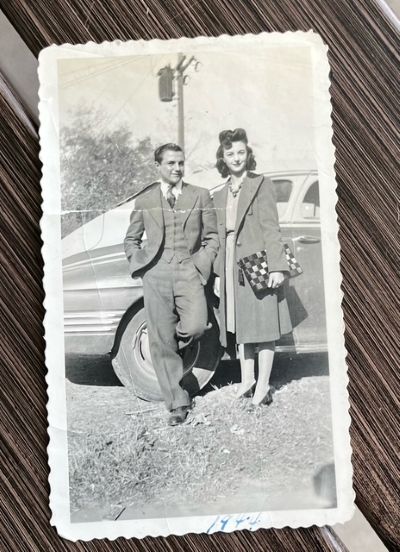

Patrick Campesi’s great-grandfather Joseph Campesi with parents, Vincenzo and Gaetana

Tell us about your background and connection to your heritage.

My great-great-grandparents Vincenzo and Gaetana came to America in 1890 from Sicily because there were not many job opportunities for them in Sicily.

Some of the families stayed in New Orleans, and not long after that, the other half went up to what’s called Iberville Parish, where I was born and raised. We moved up there probably in the early 1900s.

We were sugarcane farmers there until the 1927 flood, which pushed us more toward the river. Once that flood happened, the levee broke, water crested, and my family worked with the Army Corps of Engineers in our little town to rebuild the levee. Half of the men in the family used the mules and the donkeys to help rebuild the levee with whatever forming equipment we had. The other half went down to some smaller towns in Louisiana to trade fur and provide for the family. It wasn’t long after that, after the Great Depression, my family moved further south, about 15 minutes by car now to White Castle, and that’s where I was really brought up.

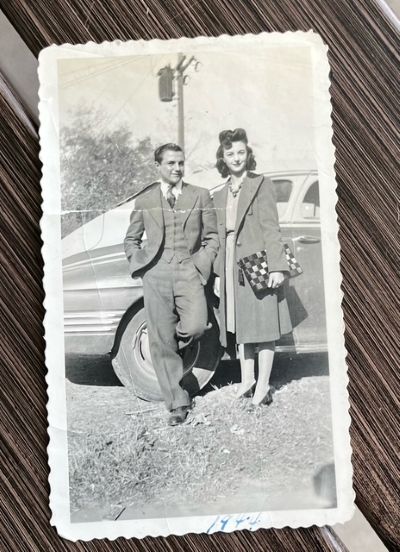

My connection to all of this was my grandfather Ross Joseph Campesi. He was born in 1925. He grew up farming sugarcane, but he was the one who really took the family from tenant farmers to owning the land. He started building businesses from there, and with only a high school education, achieved the American dream.

Poggioreale, Sicily

I was 18 when he passed, so I knew him for a good portion of my life, and he always would talk about how we’re Sicilian. We’re from Poggioreale, and there’s an organization called Poggioreale in America. I didn’t realize that there were other Poggiorealesi in America outside of my family. We grew up in what they called the Campesi Compound. I was with my uncles, cousins, and everyone in that area. I was just so confined to that little box. But then I found this organization, and this opened my world up.

My grandfather would say, “Family first, always.” It is something that stuck with me and was very impactful to me.

Once he passed, and as we entered the pandemic, I started learning more about the family, genealogy, and history. My dad was telling me more and more stories; I was just more interested in it.

Not long after that, I reached out to a gentleman named Charles Marsala, who is very involved in Louisiana. He’s been my mentor and has brought me through the ranks, introducing me to people like Marianna Gatto, Basil Russo, and John Viola, the Italians pushing to get young Italian Americans involved again. And I’ve been very lucky because of that.

I was instituted as President of the St. Expedite Lodge of the Order ISDA. That was my first foray into any type of nonprofit cultural leadership position. From there, I was elected Vice President of the Federation of the Southeast. Then, two years ago, I started the Louisiana Italian-American Heritage Foundation. Lastly, from 2024 to 2025, I was Chairman of the Italian American Future Leaders. It’s been a busy four years, but I wouldn’t change it for the world.

Tell us about St. Expedite Lodge Order ISDA and your role.

St. Expedite Lodge of the Order ISDA is a local chapter of ISDA. I was put in as vice president in 2021, and then the president ended up stepping down. He said, “Look, you’re really the one who’s pushing to get the younger people into it; you should take the presidency.”

I had to bring together people that I knew at the time, four years ago, to help create an organization. Some of the roster has changed; now, it’s just an amazing group of people. They’re hardworking.

A group of us went to the Italian American Future Leaders Convention. We typically go down to New Orleans a couple of times a quarter, and we’ll see Louis Prima’s daughter Lena Prima perform and maybe go to an Italian restaurant. Our focus is on social events for young professionals. But we do have events like a Christmas event at a place called Houmas House, where we have people of all ages. We want anybody who is Italian or Italian-loving to celebrate the culture with us here.

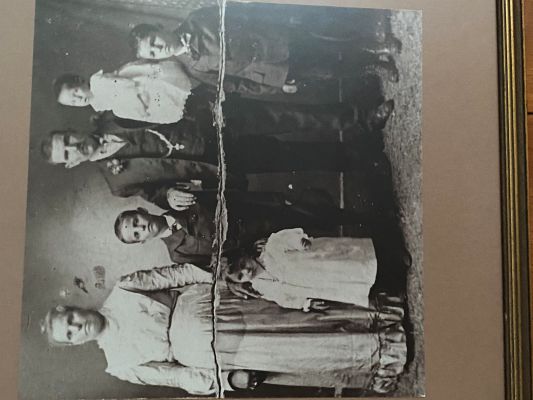

Patrick’s great-grandparents, Margherita and Joseph, in the sugarcane fields where the family worked

How did the Louisiana Italian-American Heritage Foundation start, and what is your vision as President?

I started that in December of 2023. It began as a political action committee, but because I’m in finance now, I can’t be involved in any PACs. We pivoted straight to a nonprofit, and we focus more on fundraising and some lobbying, but not directly like a PAC.

One of the main things we’re focusing on right now is fundraising for a monument to the Sicilian sugarcane harvester. So my family obviously came over here and did that. A lot of Sicilians came over and contributed to the growth of sugarcane production, not just in Louisiana but across the country and the world.

My grandfather worked with Louisiana State University to go around the world teaching third-world countries how to actually cultivate a better crop and to have a better yield. We lucked out in that, being here in Louisiana with such great soil. So he was teaching those practices, but that’s a direct contribution just for my family, not to mention all the other Sicilians who came here and did that.

Another thing that we’re doing is the Heritage Commission. New Jersey has established the New Jersey Italian American Heritage Commission, a piece of legislation that gets passed. It’s a commission that the New Jersey State government established. It’s not appropriated in any funds by the state. They have internal fundraising or grants from the Italian government. They create coursework that they can provide for schools to teach Italian contributions and Italian history here in America. One of the videos is about the relationship between Italy and America, as far as Amerigo Vespucci (we’re named after an Italian), how the American government is mimicking the Italian Republic, our accounting system, and all these everyday different contributions with an Italian root. That’s something we want to bring to Louisiana.

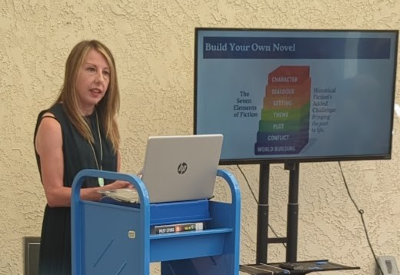

Share more about your involvement with the Italian American Future Leaders.

It is like a melting pot and a mastermind group where people come from all different walks of life, from 21 to 35, with all different experiences. Whether they run organizations or are members of them or have ideas for social media, it’s a way for all of us to come together and say, “Hey, I was dealing with something with my lodge in Louisiana; how did you do it in Indiana?” And that’s real-life experience. There’s a guy who does amazing festivals up there, and he’s helped coach us on how to do some of the feasts we do down here. So it’s just a great way for us to connect and network.

What led me to want to get involved with it? I’m a people person. I like to be connected. I like to network with people and to share in our culture. It’s something that’s so beautiful but will die out if we don’t pass it on to the next generation.

As far as leadership was concerned, I saw something great and wanted to be a part of it. But it wasn’t just me. There was a team of people that I was working with, and even while I was chairman, a lot of people helped us put together that conference that we have every year. But just to be a part of something like that and to learn from all the Basil Russos, John Violas, and Pat O’Boyles of the world, who have done so much for the community in their lifetime, but even more so with IAFL, has just been an amazing experience.

Attracting younger generations is a challenge for cultural organizations. How are you working to overcome that?

It’s difficult across the board. One of the things we’ve found is that having leadership positions available for the younger people makes a difference. Representing the young Italians of Louisiana and having the positions I have shows others that if you are active in this, this is also something that you can attain.

In many of these older organizations, the old guard doesn’t want to hand over the baton; it could be more vanity or ego. As Italians, we’re sometimes guilty of that; we’re also competitive. When you have an older organization that’s strong but won’t allow younger people to participate, well, they’re going to start their own thing, and now you’re splitting the community you’re trying to bring together. So it is not really fruitful for anybody.

It’s important to have good mentors who help bring you up through the ranks and introduce you to the people that you need to know if you were to take that position, so you’re not thrown to the wolves. I’ve mentioned Charles Marsala because he’s just been such a huge part of my life in the Italian world. Working with him was the first time I’d ever been in a nonprofit and working in any type of leadership. So I had to learn a lot of stuff, but he taught me the ropes. He had somebody who taught him the ropes, so it’s like them reaching out that hand.

Many younger Italian Americans looking for that identity, and our culture and community will take that offering, that olive branch, if you will, and get more active. One thing that we do is just have events that people want to go to. We want to keep an air of tradition and culture while making it modern and attractive for a young Italian professional to actually want to come to the events, keeping it upbeat but still maintaining that central tradition and culture we all collectively share.

What initiatives or programs are you most proud of implementing or supporting?

I’m a very proud Italian American from Louisiana. When people think of Italian Americans, they think of New Jersey and New York, but they forget about California, Florida, and everybody across the country. But we’re here, just a different flavor of the Italian American pie. So one of the things I’m most proud of, outside of just seeing the growth of IFL last year, was the Louisiana delegation that we had come in. Some people I was very close with, and some I didn’t even know were from Louisiana, and they showed up there. Now, we’ve got our group, which has experienced IAFL, and we represented Louisiana very well.

Outside of that, locally with the St. Expedite Lodge, it’s just the growth that we’ve had, not only in total membership but also with leaders who want to take action, take part, and take responsibility in the development of this organization. We now have a marketing department that works on social media, whether it be Instagram posts, Instagram Reels, or Stories, trying just to have content continuously put out there, not just something to put out there, but something meaningful. We have an event coordinating department as well, which is planning the Spring Serata.

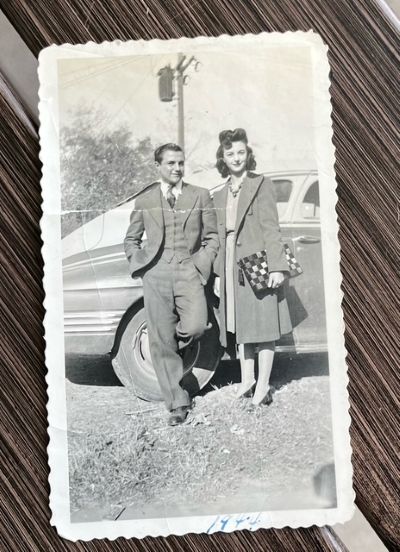

Patrick’s grandfather Ross with cousin Grace Cannizzaro

What do you hope to share with your community?

It’s multifaceted, for one, as I look back to the little enclaves here in Louisiana. We used to have the little Italys across the French Quarter. It used to be called Little Palermo. There were so many Sicilians and Italians there, but as people age, they move out, die out, or become more successful because their families saved enough money to send them to school. They wanted a better life, and when they moved out, that community disappeared.

I want to bring that community back, not just locally, but on a national scale where it’s a national enclave, not just limited to Louisiana. I think IAFL is the perfect breeding ground for that.

I got stuck in New York two years ago on a flight back from Italy. I had some friends I met from IAFL who drove in from Massachusetts, and I had people who stayed with me for one day, took me around, and showed me around the area. I would never have known them and never would’ve been able to experience that had I not been at IAFL. Another example was when I was in New Orleans last October. Two friends, one from North Carolina and the other from New Jersey, came down for our film festival. Sure enough, we met another guy who happened to be in New Orleans and had attended IAFL the year before from Texas. We all just got coffee and beignets in the French Quarter.

It’s just bringing that community together. And I think outside of just the local sense of things, we’re in a digital age where network is just so much more expansive, and that’s something that I’d like to bring for us here is not just in Louisiana, but being able to help a friend who wants to maybe move to New Orleans or who wants to open a business or has a connection that I have here that could benefit them. I’d like to be able to expand that. We will bring that back together, but on a national scale.

If you enjoyed this article, consider subscribing to my newsletter for more content and updates!